Revolutionary Norwegian rescue plan locks enormous quantity of CO2 underground

The question of how to capture excess CO2 from the atmosphere and store it securely below-ground is one with which scientists, entrepreneurs and politicians have long been grappling. It is also one which is in urgent need of an answer, since the objective that has been set is to halve annual greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. A number of countries are already storing carbon beneath the sea, but in Norway an even more ambitious solution is coming to fruition.

This carbon capture and storage (CCS) project for industrial CO2, which to many seems a long-distant future scenario, goes by the name of Longship and should provide open access to infrastructure with the aim and ability to store a remarkable amount of CO2 from all over mainland Europe.

“In September 2020, Norway’s previous government decided to launch the Longship project,” explained Tove Dahl Mustad, the director of benefit realisation and business development at Gassnova, the Norwegian state enterprise for CCS. “It’s the biggest climate project that’s ever been undertaken in the Norwegian industrial sector and the first CCS project in Europe based on the latest European legislation.”

The Longship project, 80% of the financing for which is coming from the Norwegian government, will go into operation as soon as 2024 and show the way in the development of technology which could prove decisive in achieving climate goals.

Mustad says the project involves the collection of CO2 from the Norcem cement factory and Celsio waste-to-energy plants, followed by its transporting by ship for permanent geological storage.

Dr Aage Stangeland, a special adviser to the Research Council of Norway, says the country has many years of experience in storing carbon at the bottom of the sea, which will be of benefit in the Longship project.

Namely, gas and oil have been pumped from the North Sea for decades. “Norway discovered pockets of natural gas below the sea bed years ago, but it contained a huge amount of CO2, so no one was interested in buying it,” Stangeland said.

To be able to sell the gas, the CO2 had to be removed from it. There were two ways of achieving this: allowing it to be emitted into the atmosphere; or storing it at the bottom of the sea.

Releasing the carbon into the atmosphere would have proven too costly, since there is a very high emissions tax in Norway because of the country’s gas and oil industry. As such, it was cheaper for the company to deposit the carbon underwater.

Saltwater reservoirs instead of gas and oil reservoirs

Stangeland says the Longship project represents another small step forward as it is about capturing carbon from industry. “It will then be transported by ship to the North Sea, where it will be piped down into the depths to be stored in geologically suitable porous rock strata beneath the sea bed,” he explained.

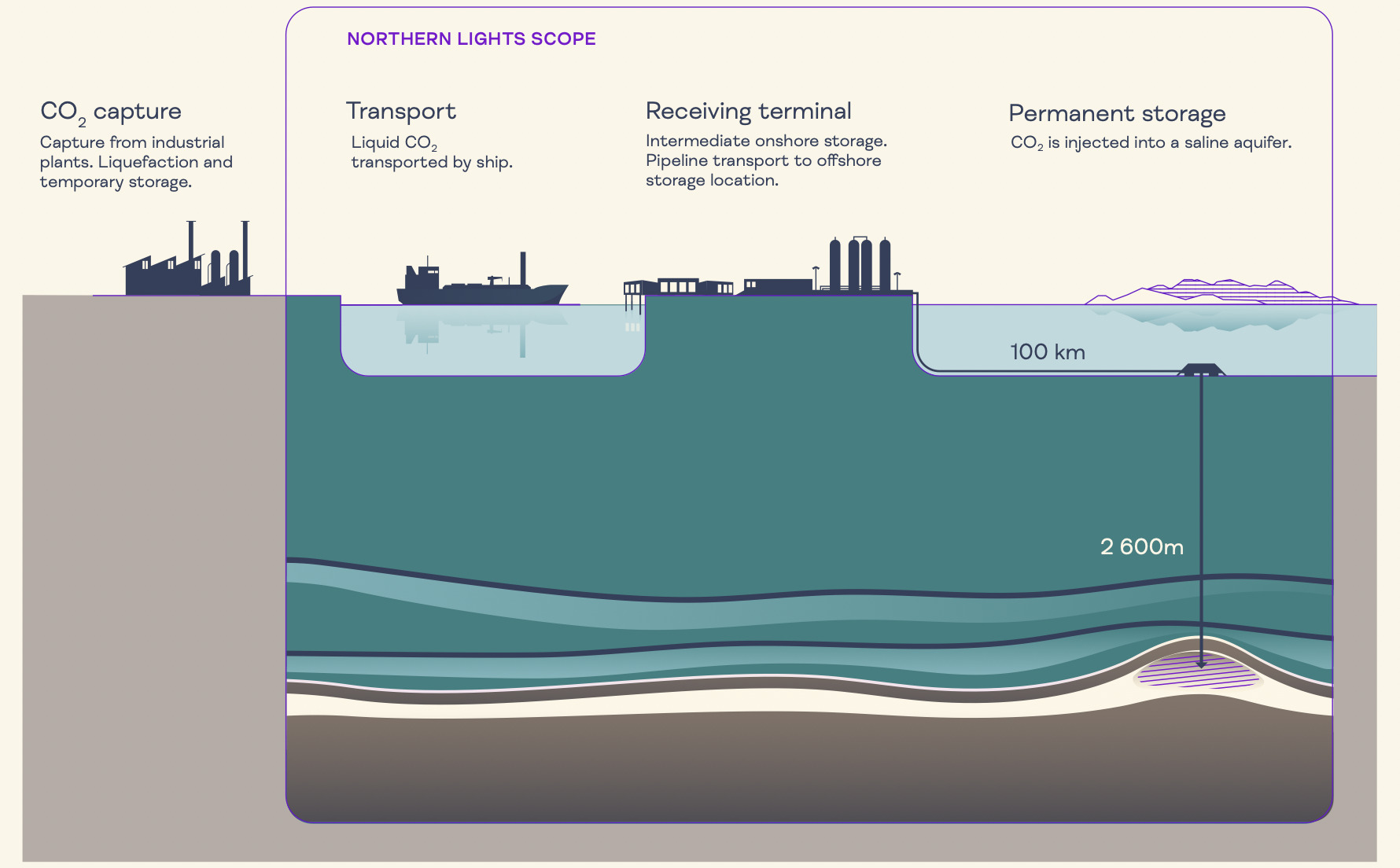

Responsible for providing these transport and storage services will be Northern Lights, a joint undertaking of Equinor, Shell and TotalEnergies. Its head of communications and government relations, Kim Bye Bruun, says the company will be collecting CO2 from two receiving terminals being built in Øygarden municipality in Western Norway. “It will then be transported by two ships to a point 100 km from the coast, where it will be stored 2600 metres beneath the sea,” he explained. “The ships taking it there will be purpose-built, and in fact be the biggest maritime transport vessels for CO2 ever constructed.”

The CO2 will be stored as indicated in this illustration.

Image: Norlights.com

The only project of its kind in the world

Taking their lead from Norway, three other countries – Denmark, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom – are making preparations to store CO2 in former gas and oil reservoirs. Similar options are being investigated in Canada, Australia and the United States.

In Japan, a proportion of captured CO2 has already been stored in empty gas and oil pockets at the bottom of the sea. But what makes the Norwegian project unique is that its CO2 is to be stored in underground reservoirs currently filled with saltwater, which the carbon will replace.

The first phase of development, which should commence in mid-2024, promises annual storage capacity of 1.5 million tonnes of CO2 in these natural reservoirs.

Bruun says that what they are dealing with in reality is a sandstone reservoir. “If you imagine how such a thing looks, then putting it simply, you might compare it to beach sand that’s been very tightly compacted,” he said. “The entire reservoir is really porous, which is what gives us the space we need to store the CO2. And the CO2 in turn has space to move within the reservoir, meaning that in time we’ll be able to store more carbon in it.”

Stangeland says that in addition to the sandstone, less porous stone is needed that will stop the stored CO2 from leaking into the water or atmosphere. “Various points in the North Sea meet both those conditions, which is why Norway and other countries in the region, like Denmark and the UK, have somewhere to store their CO2.”

A CO2 receiving terminal is under construction in Øygarden. This photo was taken at the site in September 2021. Image: Norlights.com

Exponential rise in storage volume

As early as its second phase, the project will see annual storage capacity of 5-7 million tonnes of CO2.

It is anticipated that 37.5 million tonnes of carbon will have been stored in the North Sea reservoir by 2049. “Over a period of a couple of thousand years, that carbon is likely to make its way into the area from which Norway’s been drilling for gas and oil,” Bruun explained. “It will become trapped there in the exact same way the oil and gas were trapped there for millennia.”

The ships, which are also due for completion by 2024, are expected to be the biggest CO2 transport vessels ever constructed. “Each ship will be able to take on 8000 tonnes of CO2,” Bruun said. “No doubt even bigger ships will be built in the future, but based on what we know today, ours will be the biggest ever seen when they go into operation.”

Knowledge to be shared with anyone interested

Since Northern Lights will have the ability to store CO2 from sources other than Norcem and Celsio from 2024 and has plans to increase its capacity from 1.5 million tonnes to 5-7 million tonnes, the company is willing to get other interested cement and waste industry players involved in the second phase.

Thea Tanberg, an adviser to the Norwegian Ministry of Petroleum and Energy, says the main aim of the Longship project is to show that CCS is both safe and feasible and that it can be implemented in full. “The fact the project is in the preparatory phase and will be capturing and permanently storing CO2 as planned starting from the second half of 2024 will hopefully show others that full-scale CCS is not only possible, but already being done,” she said.

In order for the project to spread as a measure for mitigating climate change, the experts agree that other countries and similar projects need to get involved in Longship.

“We have no desire or intention to keep this knowhow to ourselves,” Bruun said. “If we did, the project could be considered a failure, since we want to share what we know and because our main aim is to reduce CO2 emissions globally.”

Nevertheless, Mustad adds that the London protocol forbids the transporting of CO2 across borders unless certain conditions are met. “If the exporting and importing countries have ratified the amendments to the protocol made in 2009, they can agree on moving their CO2 across borders,” she explained. “Norway and Estonia have both ratified the amendment.”

This means that if Northern Lights and an Estonian source of emissions wished to enter into a commercial agreement, the governments of their two countries would have to sign a bilateral agreement prior to the CO2 being transported.

A rendering of how the Øygarden receiving terminal – whose capacity will increase to up to 5 million tonnes of CO2 annually in the second phase – may look if expanded. Image: Norlights.com

Could Estonia benefit from Norway’s success?

TalTech professor Alar Konist says praise is due to the Norwegians for being one of Europe’s biggest producers of renewable energy despite also being one of its biggest producers of fossil fuels.

“What that means of course is that they have the cashflow needed to invest in and look at ways of substantially reducing environmental impact,” he said.

In Konist’s view, Estonia could and should contribute more to both of these areas. “Because there are places here that are generating a large amount of CO2 as well,” he explained. “We could partner with Norway on that, because they already have the knowhow. We certainly want to work with them, and I’m sure they’d be happy to work with us as well.” This was confirmed by Bruun, who said that they have been in contact with Estonian industrial companies interested in joining the second phase of the project.

Tanberg says the Norwegian government also deals with matters related to such bilateral agreements. “In general, Norwegian CCS projects can also be supported through the EMP and Norwegian grants,” she explained.

The Norcem cement factory in Brevik is Northern Lights’ first client. Image: Norlights.com

Can we be sure the CO2 won’t leak from the reservoirs?

Tanberg says it is difficult to answer the question of what danger, if any, earthquakes pose to the reservoir. “It depends on the scale and location of the quake and how much surface damage it causes,” she said.

Konist adds that a pragmatic view needs to be taken of the threat of earthquakes, since all storage sites are easily monitored. “The existing sites are so deep that they also have oceanic pressure bearing down on them from above, which all but rules out the risk of a substantial leak,” he explained.

Stangeland agrees that the North Sea storage sites are quite safe, since the area is not subject to earthquakes. “That said, geological surveying does need to be carried out, because if you store the captured carbon in pockets that have natural cracks in them, then you might get a leak,” he cautioned. “Those are the sorts of dangers that need to be ruled out ahead of time by conducting surveys and studies.”

According to Stangeland, similar technology is being tested in Japan. “They succeeded in storing carbon in the course of their pilot project,” he said. “They even had a strong earthquake while they were doing it, after which they took lots of measurements that showed it hadn’t resulted in a single leak.”

Mustad adds that although risks do exist, they are the same as those faced by the gas and oil industry. “And Norway has decades of experience in that regard,” she said.

According to surveys, the reservoirs off the coast of Norway could accommodate as much as 80 billion tonnes of CO2 – the equivalent of 1000 years’ worth of Norway’s current carbon emissions.

In cooperation with the news portal Geenius, the Norwegian embassy in Estonia and other Nordic embassies in the country, we launched a series of articles in which we shed light on the Nordic economies of the future and cooperation between Estonia and its Nordic neighbours. The articles can be found online at https://ari.geenius.ee/blogi/pohjamaade-tulevikumajanduse-blogi/.